Author

Educator

My work is focused on solutions to help students, educators, administrators and community members and their organizations/institutions thrive, not just survive.

My work is focused on solutions to help students, educators, administrators and community members and their organizations/institutions thrive, not just survive.

Pre-Pandemic, I spent much of my time at disaster sites, helping students, educators and institutions find pathways forward following a traumatic event. Whether it was a concert massacre or a border detention facility or a school shooting, I worked with individuals and organizations where trauma abounded. One lesson I learned was that to do this disaster relief work, I had to exercise self-care because, as the saying goes, you can’t pour from an empty cup.

Through a combination of making a mess with paints, expressing visually what I could not address verbally and exploring color, I created art. It was not originally designed to address trauma explicitly; it was designed to help me ameliorate the trauma I was witnessing (and to be candid, had witnessed throughout my life). And, to be clear, I was not a trained artist in any sense; I took one life drawing class in 1996!

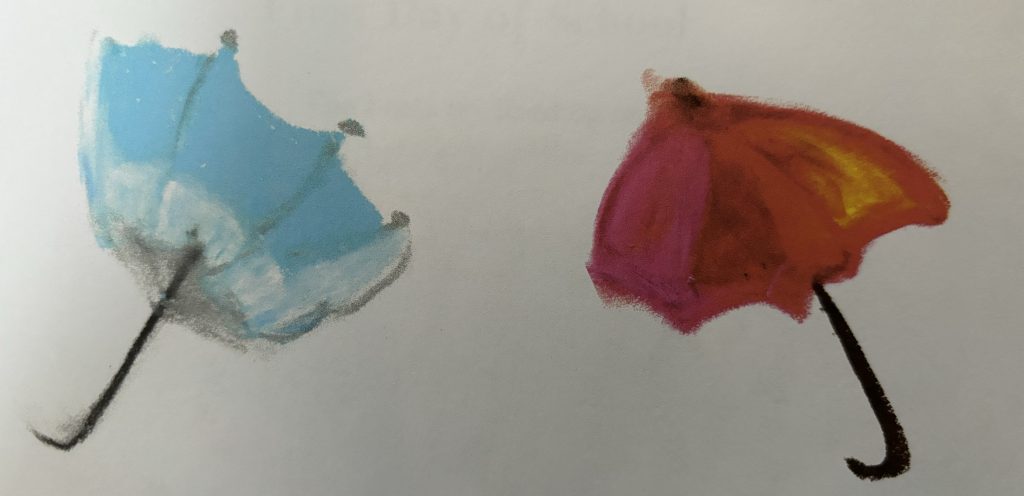

Here are two examples of my early pre-Pandemic art that appear in a published book of poetry I wrote for children (and adults) titled Flying Umbrellas and Red Boats published in 2019.

Karen Gross, Red Boat Alone at Sea (2018)

Karen Gross, Flying Umbrellas (2018)

But, along came the Pandemic and the omnipresence of trauma across the globe. It was during those early months that my engagement in and with art changed. With an unanticipated intensity, I created art that reflected the abundance of illness, death and dying as well as isolation, confusion and complexity with which we were living.

Let me explain.

For me, textured art took on new meaning. Collages moved to the forefront of my efforts. This was in part a response to the world in which we were living – it was filled with bumps. Our lives were far from smooth, and my art reflected the absence of that smoothness. And it showcased the intermixture of feelings and situations that both adults and children were feeling.

Here’s a sampling of my early Pandemic art, reflecting at least for me, the larger issues in our world.

Karen Gross, Cluttered and Then Some (2021)

Karen Gross, We’re Cracked (2021)

Although I continued my art in private, I started sharing my art; it hung on the walls of my home. It appeared in juried online and in person shows. I added it to my blog posts. And then, I included “doing” art with children and adults in the classes I taught remotely and later in person during the Pandemic. This art took many forms.

I tried using art to illustrate what trauma was doing to us – how it was dysregulating us and creating a sense of uncertainty and disorganization. The goal was to give visual cues as to what was occurring within our minds. While I continued to write books and blogs, I saw art as another pathway through which to share trauma’s profound effects near and longer term.

Consider this example.

Karen Gross, A Messy Mess (2023)

Then, I saw a need to illustrate how current trauma trips off earlier trauma, setting off a host of intense reactions. I called these tuning forks as our response to trauma mirrored the physics principles of action and reaction. The reverberations got stronger with each touch of the fork. When many forks were activated, I referred to it as “tuning fork orchestras.” And to this day, I keep a fork near me as I work, reminding me of trauma’s retriggering power. I reference tuning forks when I talk to professionals about trauma anniversaries and memorials.

Consider this example of “tuning fork art.” The first one is truly an orchestra – with the turning forks appears vertically and horizontally. The second piece is an homage to the memoir Viola Ford Fletcher published titled Don’t Let Them Bury my Story (2023)

Karen Gross, Turning Forks Galore (2022)

Karen Gross, Viola Ford Fletcher’s Story (2024)

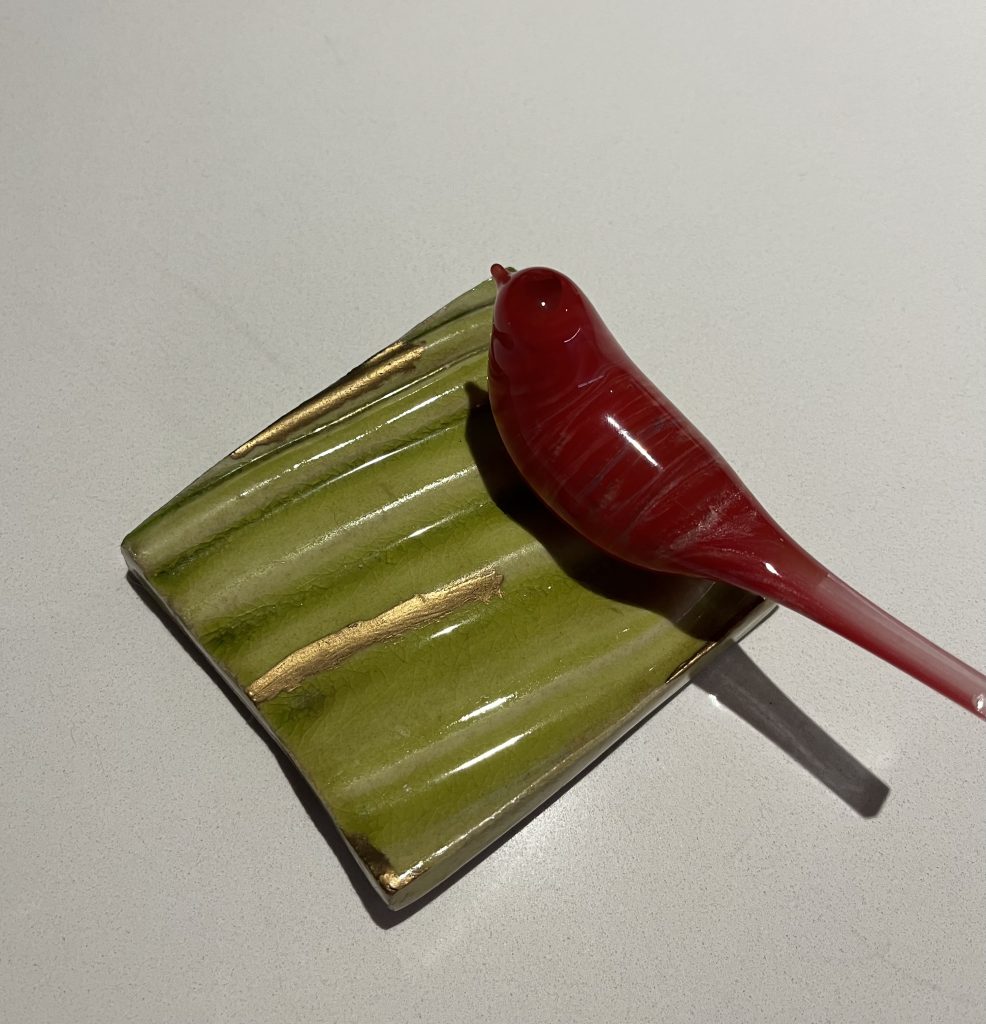

Along the way, I introduced students to Kintsugi art – both seeing it and creating it. The idea was to take what was broken and mend it, uttering the phrase used in Kintsugi art, “more beautiful for being broken.” I shared Kitsugi motivated art that I created (I termed it “making peace of pieces”). I actually broke and mended bowls with educators who experienced trauma. Here are some examples.

Karen Gross, Repaired Lid with Bird (2022)

Sample of materials used with students and adults to repair broken bowls and plates (2020 – 2024)

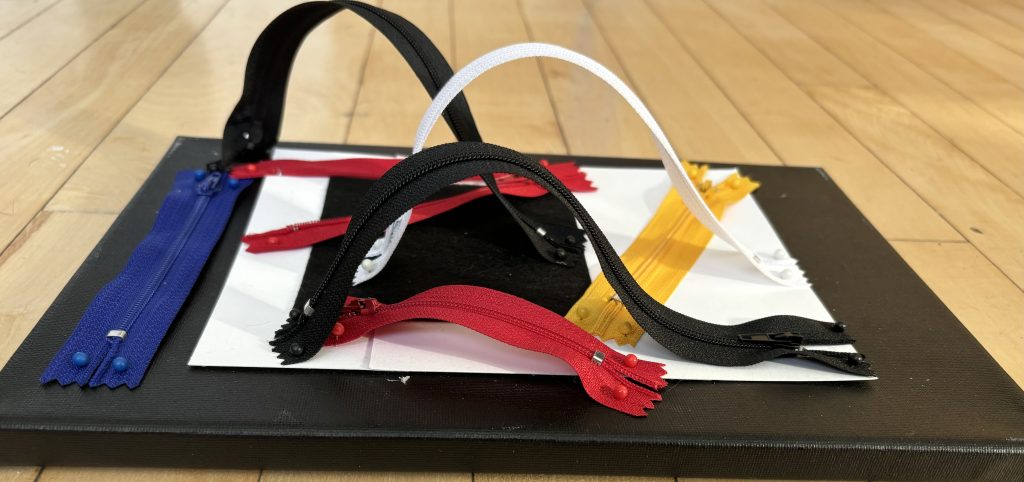

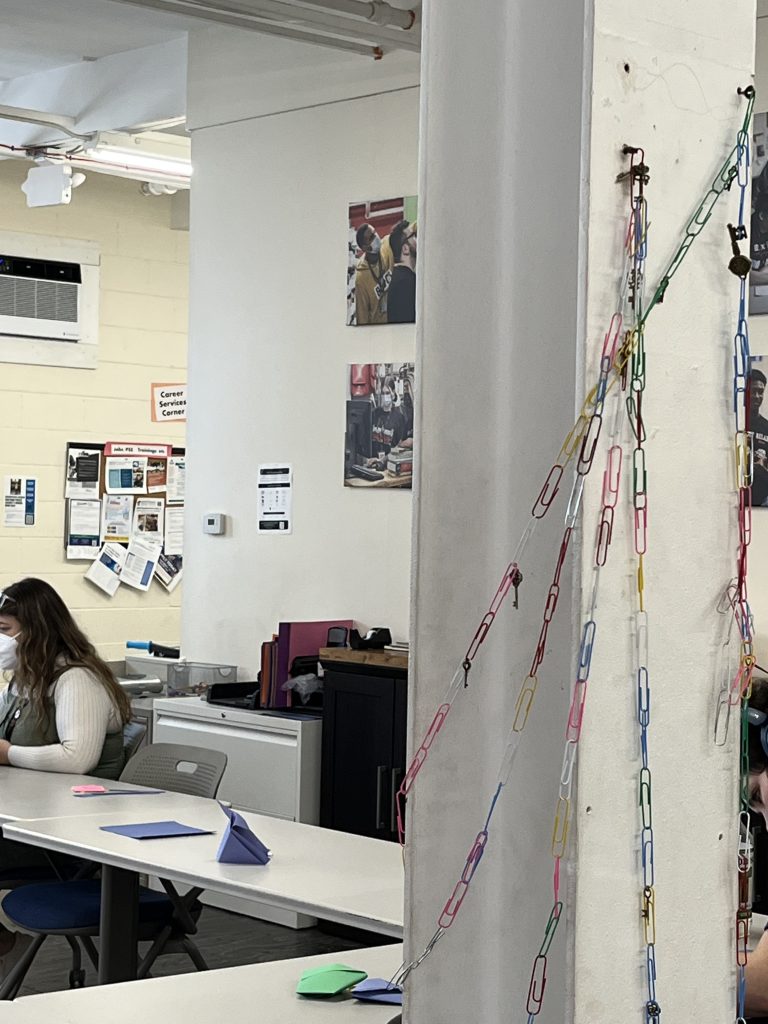

Our art then took different forms, all reflective of the Pandemic and its impact upon us all. We created Kindness Rocks that were then given away to activate empathy engines. We created paperclip art chains that were strung around furniture and people to showcase the value of connection. We utilized zippers that reflected whether we were emotionally zipped up or totally unzipped. We did art on walls and in halls. All these art efforts were designed to respond to trauma by activating the senses and encouraging imagination but also to ameliorate trauma’s symptoms, focusing on connection and mending. It is this latter theme that accounts for the title of the new book I co-authored with Edward K.S. Wang, Mending Education: Finding Hope, Creativity and Mental Wellness in Times of Trauma (Teachers College Press, 2024). And, the book is full of our art, both to showcase points we make in the text itself and to reflect the import of creativity on healing and moving forward in difficult times. In a sense, this book combines theory, practice and art to enable mending that endures.

Consider these examples:

Kindness Rocks created by elementary school students in Danvers, MA (2024) and displayed at Martin Luther King Day event.

Example of Zipper Art à la Miro style (2023)

Paperclip Art created at Massachusetts non-profit that provides assistance to youth (2022)

Karen Gross, Mending Art (2024)

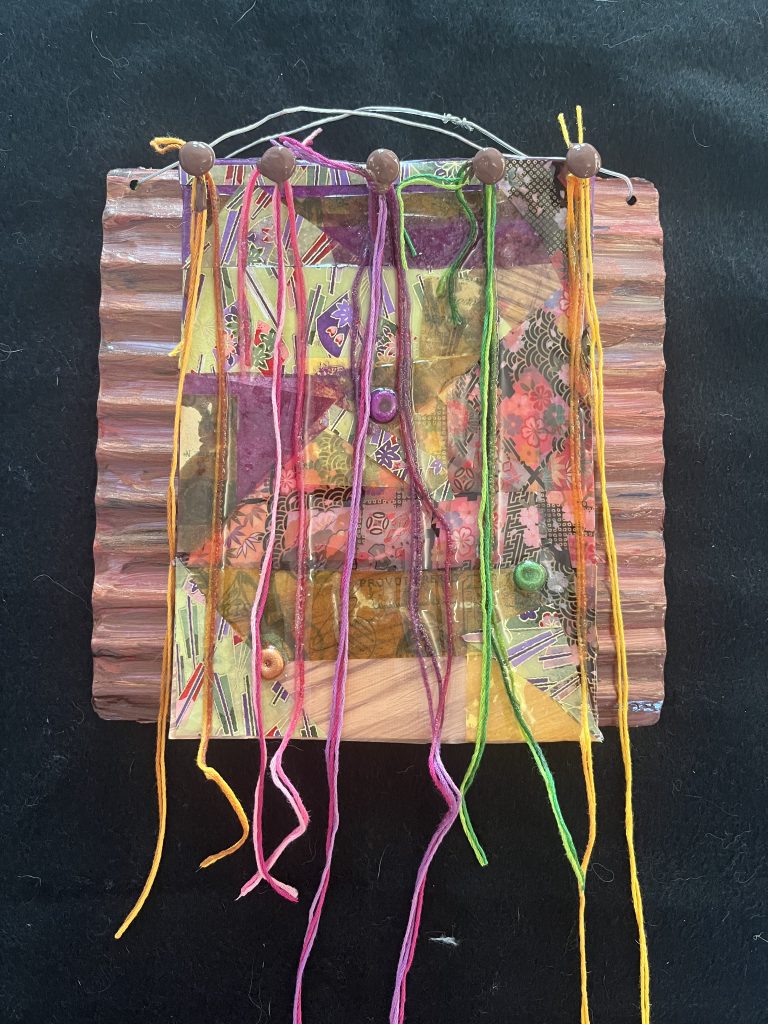

Common Objects

Much of the art displayed here uses common objects, making it vastly easier for students and educators to find: forks, zippers, buttons, thread, yarn, rocks, paperclips, labels, glue and paint. With these common objects, we can create art that responds to the trauma we are experiencing – both representing the trauma itself and our pathways forward through mending.

As my students of all ages used art, I too expanded my art repertoire. I, too, used shards and common objects. I used ripped paper and glue. I used plaster of paris; I made fragile bowls and when they broke, I turned them into Georgia O’Keefe-esq sculptures. I used things that were discarded. And from the detritus, I created art that messages. And I shared it with students and educators.

Karen Gross, Fragile Bowl

Karen Gross, Georgia O’Keefe Series 1 (2022)

Art can help us both recognize and ameliorate trauma. I cannot think of anything more powerful than enabling all individuals to move forward through difficult times. Art is one strategy for doing that. We would be wise to recognize art’s power and not marginalize it. Art, as described here, is not static; it is created to help move people and in that effort, it allows all of us to see and experience the effects of creativity and the power of the possible.

And, to that end, here is one final piece of art, exemplifying the themes presented here. Emotional stress, dangling with uncertainty, piecing things together and finding beauty. Some say we are living in a VUCA world – with the letters standing (depending on the source) for volatile, uncertain, chaotic and anxiety-provoking. And, if you are doing trauma art—whether for yourself or for your students—reach out. I’d welcome that. Share it. It will help us all.

Karen Gross, Dangling by Threads (2023)