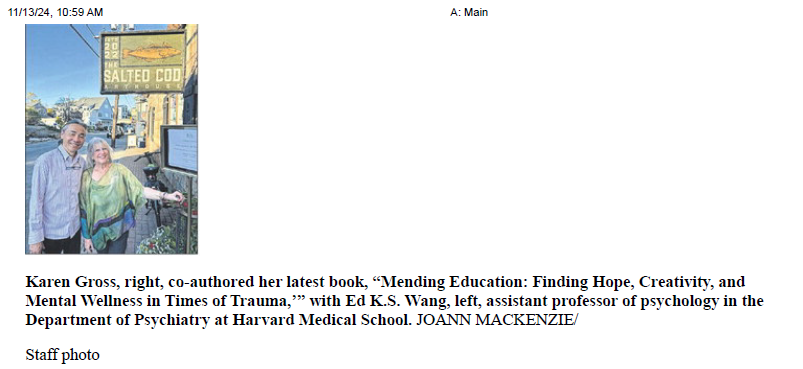

Author

Educator

My work is focused on solutions to help students, educators and their institutions to thrive, not just survive.

My work is focused on solutions to help students, educators and their institutions to thrive, not just survive.

Last night, we held our monthly meeting of the Virtual Teachers Lounge (VTL), a non-partisan group that gives educators across the K-12 landscape a safe space in which to share what is going on in their classrooms, their schools and their districts. The VTL was created during the Pandemic, when brick and mortar teacher lounges were shuttered, and educators needed a safe place to convene with other educators. There are six of us who form the VTL leadership core. We offer our online venue for free. All educators, from across the globe, are welcome to attend. You can find us at www.vtl4today.com.

Usually, our monthly get-togethers are dialogic. We offer monthly tips (based on the acknowledged themes/holidays of the month in question that can be used in classrooms). Then, we pose a prompt or two (in advance or on the spot) and converse and share. About 25–50 people attend each month.

Last night was different. I had agreed, since I worked in the Department of Education (7th floor for those in the know) during the Obama Administration, to share what the cratering of the US Department of Education means for schools, teachers and students … and yes, States. To that end, I prepared a slide deck that I said was available to any registrant after the event. The PowerPoints detailed, as best as I was able, what the Department of Education does (did) and the impact being felt now (in real time) and down the road by the massive cuts of a wide ranging sort (of $$ and people) across the nation.

The presentation was intended to be, and I think was, factual. Many people, educators included, actually do not know all or even some of what the Department of Education does (did) at the micro, meso and macro levels. It is hard to do an impact analysis of its demise if the actual role/functions of the Department are not understood.

After the description of the major work fields within the Department, I provided a sampling of just some of the impacts of the current cuts and cutbacks, particularly on teachers (given we are the Virtual TEACHERS Lounge). (I did note other impacts on students that can be felt beyond those being engendered by the Department of Education cuts.) I then detailed some of the current efforts to reverse the cuts both within and outside the legal arena.

Just the facts.

It was only at the very end of the presentation that I shared possible additional approaches in which VTL and individuals and organizations could engage to stem the harms being wrought on literally millions upon millions of students and teachers.

In the chat (which we run simultaneously during the sessions), one attendee asked this: What explains the Administration’s behavior with respect to education writ large and the Department of Education in particular? The comment added: “It can’t just be saving money.” What a good question and I answered it last night.

But, I want to answer it even more fully here for all to read and ponder. Call this an expanded version of what I shared on VTL last evening.

My answer is formed on the basis of my in-the-trenches experiences in education (from early childhood to adult) over decades but also what I have seen, heard and read of late, including most particularly a stunning article by Harvard Law School Professor Jeanne Suk Gersen that appeared on April 15, 2025 in The New Yorker. (I am sharing a link to that article with VTL attendees when they receive the slide deck.)

The Suk Gersen article is focused on higher education; I am applying many of its ideas to the pre-K through 12 arena and the Department of Education itself.

Let me start by saying that the dismantling within education is not about saving money, although some monies may be saved short-term. Nor is the dismantling about stopping antisemitism. Both savings (streamlining the federal bureaucracy) and a rooting out of deep seeded antisemitism are the commonly cited explanations for what is occurring when “our” current leaders seek to attack educational institutions that serve students both from the US and across the world. Under the guise of savings and promoting antisemitism (and protecting Jewish students), there is an effort to increase the “policing” of schools, colleges and universities in the name of eradicating discrimination.

But, here’s the point: The actual goals are not as described and articulated. There is a much deeper and I’d say perverse set of explanations for why the US government is trashing federal education supports and educational institutions themselves. (And yes, the President asked the IRS to revoke Harvard’s non-profit status, an act that no president can do unilaterally, an observation keyed to what follows.)

Here’s my description of what actually undergirds the demise of the US Department of Education. Through profound changes to student grants/loans and the terms of loan repayment, to the virtual eradication of the Office of Civil Rights within the Department of Education, to the almost complete elimination of data collection and research on education and its outcomes, to the stoppage of grants to schools, colleges and universities (including monies already approved but not yet allocated), there is a message: we want (we meaning the current administration) to bring educational institutions “to their knees” (to use Suk Gersen’s term), all in an effort to eradicate what could be termed collectively the “woke” movement.

Let me unravel this. Start here:

The current administration does not like the diversity of views within our educational institutions and believes that “liberal views” have squelched conservative voices. The current administration is not in favor of diversity, equity and inclusion, eradicating its use in both form and substance. The current administration believes the Department of Education fostered curricular influence and impact on state run schools/colleges/universities (although the Department of Education has never had control over curricular decision-making). The current administration does not support free speech, the hallmark of education (and many other values) and one of the reasons for tenure. The current administration believes that the banning of books in schools and libraries and now the military academies will shift ideology away from the support for diverse students and eliminate access to information (knowledge). The current administration wants to “rewrite” history (another denial of information that is true) by eradicating references in books and curricula to racial, ethnic and other struggles, including with respect to LBGTQ. The current administration has made English our nation’s official language, in large part to eliminate programs that support English language learning for students. The current administration sees no need to support teacher education in its many forms financially. The current administration does not perceive the necessity of protecting the most vulnerable among us, including children experiencing food scarcity, disabilities of a wide-ranging sort and lack of mental wellness.

In the administration’s views, all of the above is representative of “wokeness.”

Taken together, the point of dismantling the US Department of Education by this administration is threefold in my view: (1) eradicate “left” leaning ideology including by narrowing substantially access to knowledge and information; (2) give power to the states (particularly Red states), all without oversight so that these state can decide to privilege some students over others with no federal guardrails in place to insure legal compliance with our laws and Constitution; and (3) increase the power of the federal government over both public and private educational institutions (as well as non-profit organizations and BigLaw firms) by illegal threats (monetary and non-monetary) that force compliance because of draconian consequences (real or imagined), authoritarian control in short.

Let me be even clearer: The US Department of Education was created to insure that ALL students, wheresoever located or born and whatever their race, ethnicity, sexual orientation and capacity, are treated fairly and equitably and with all the needed protections our laws can provide. There is nuance here for sure in terms of the meaning of taking away dollars, eliminating research and data informed decision-making and potential changes to accreditation standards. But at the meta level, the dismantling of the US Department of Education is an existential threat to our Democracy. Read that again. Yes, when we unwrap the rhetoric and look beneath the surface, the dismantling of the US Department of Education is an existential threat to our Democracy.

That’s frightening.

Pre-Pandemic, I spent much of my time at disaster sites, helping students, educators and institutions find pathways forward following a traumatic event. Whether it was a concert massacre or a border detention facility or a school shooting, I worked with individuals and organizations where trauma abounded. One lesson I learned was that to do this disaster relief work, I had to exercise self-care because, as the saying goes, you can’t pour from an empty cup.

Through a combination of making a mess with paints, expressing visually what I could not address verbally and exploring color, I created art. It was not originally designed to address trauma explicitly; it was designed to help me ameliorate the trauma I was witnessing (and to be candid, had witnessed throughout my life). And, to be clear, I was not a trained artist in any sense; I took one life drawing class in 1996!

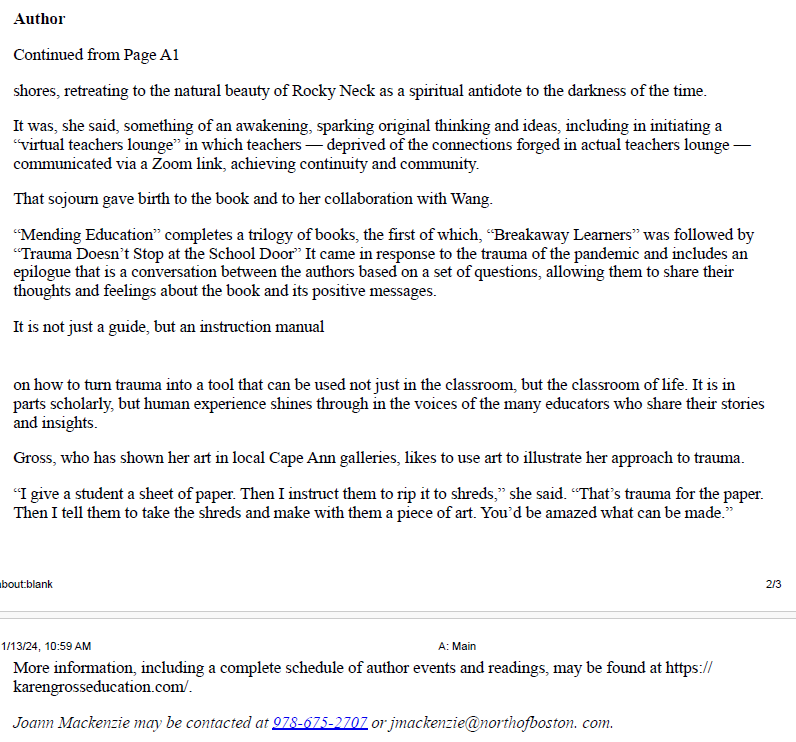

Here are two examples of my early pre-Pandemic art that appear in a published book of poetry I wrote for children (and adults) titled Flying Umbrellas and Red Boats published in 2019.

Karen Gross, Red Boat Alone at Sea (2018)

Karen Gross, Flying Umbrellas (2018)

But, along came the Pandemic and the omnipresence of trauma across the globe. It was during those early months that my engagement in and with art changed. With an unanticipated intensity, I created art that reflected the abundance of illness, death and dying as well as isolation, confusion and complexity with which we were living.

Let me explain.

For me, textured art took on new meaning. Collages moved to the forefront of my efforts. This was in part a response to the world in which we were living – it was filled with bumps. Our lives were far from smooth, and my art reflected the absence of that smoothness. And it showcased the intermixture of feelings and situations that both adults and children were feeling.

Here’s a sampling of my early Pandemic art, reflecting at least for me, the larger issues in our world.

Karen Gross, Cluttered and Then Some (2021)

Karen Gross, We’re Cracked (2021)

Although I continued my art in private, I started sharing my art; it hung on the walls of my home. It appeared in juried online and in person shows. I added it to my blog posts. And then, I included “doing” art with children and adults in the classes I taught remotely and later in person during the Pandemic. This art took many forms.

I tried using art to illustrate what trauma was doing to us – how it was dysregulating us and creating a sense of uncertainty and disorganization. The goal was to give visual cues as to what was occurring within our minds. While I continued to write books and blogs, I saw art as another pathway through which to share trauma’s profound effects near and longer term.

Consider this example.

Karen Gross, A Messy Mess (2023)

Then, I saw a need to illustrate how current trauma trips off earlier trauma, setting off a host of intense reactions. I called these tuning forks as our response to trauma mirrored the physics principles of action and reaction. The reverberations got stronger with each touch of the fork. When many forks were activated, I referred to it as “tuning fork orchestras.” And to this day, I keep a fork near me as I work, reminding me of trauma’s retriggering power. I reference tuning forks when I talk to professionals about trauma anniversaries and memorials.

Consider this example of “tuning fork art.” The first one is truly an orchestra – with the turning forks appears vertically and horizontally. The second piece is an homage to the memoir Viola Ford Fletcher published titled Don’t Let Them Bury my Story (2023)

Karen Gross, Turning Forks Galore (2022)

Karen Gross, Viola Ford Fletcher’s Story (2024)

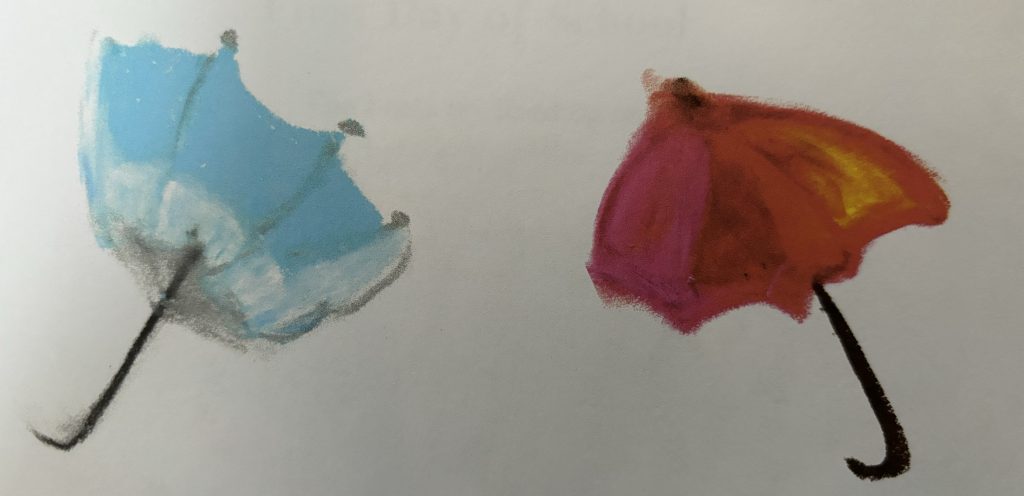

Along the way, I introduced students to Kintsugi art – both seeing it and creating it. The idea was to take what was broken and mend it, uttering the phrase used in Kintsugi art, “more beautiful for being broken.” I shared Kitsugi motivated art that I created (I termed it “making peace of pieces”). I actually broke and mended bowls with educators who experienced trauma. Here are some examples.

Karen Gross, Repaired Lid with Bird (2022)

Sample of materials used with students and adults to repair broken bowls and plates (2020 – 2024)

Our art then took different forms, all reflective of the Pandemic and its impact upon us all. We created Kindness Rocks that were then given away to activate empathy engines. We created paperclip art chains that were strung around furniture and people to showcase the value of connection. We utilized zippers that reflected whether we were emotionally zipped up or totally unzipped. We did art on walls and in halls. All these art efforts were designed to respond to trauma by activating the senses and encouraging imagination but also to ameliorate trauma’s symptoms, focusing on connection and mending. It is this latter theme that accounts for the title of the new book I co-authored with Edward K.S. Wang, Mending Education: Finding Hope, Creativity and Mental Wellness in Times of Trauma (Teachers College Press, 2024). And, the book is full of our art, both to showcase points we make in the text itself and to reflect the import of creativity on healing and moving forward in difficult times. In a sense, this book combines theory, practice and art to enable mending that endures.

Consider these examples:

Kindness Rocks created by elementary school students in Danvers, MA (2024) and displayed at Martin Luther King Day event.

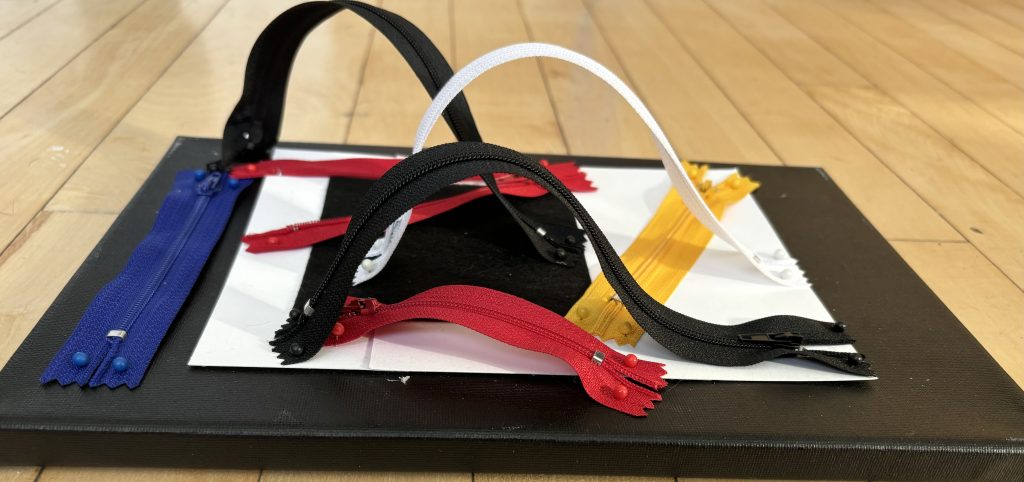

Example of Zipper Art à la Miro style (2023)

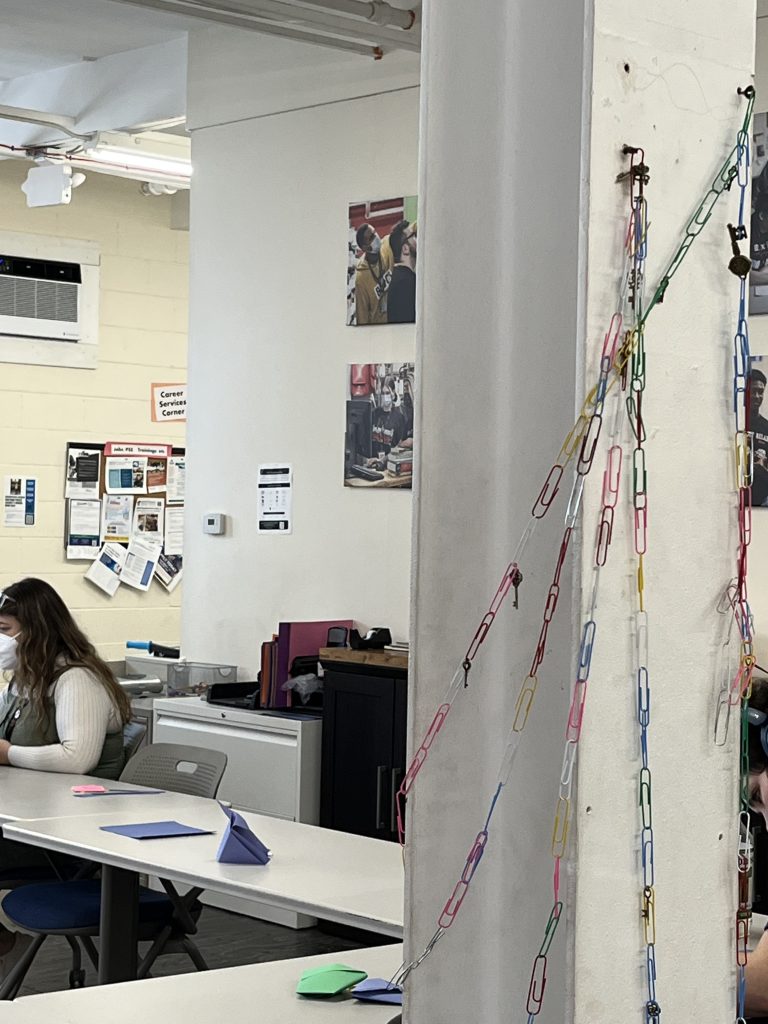

Paperclip Art created at Massachusetts non-profit that provides assistance to youth (2022)

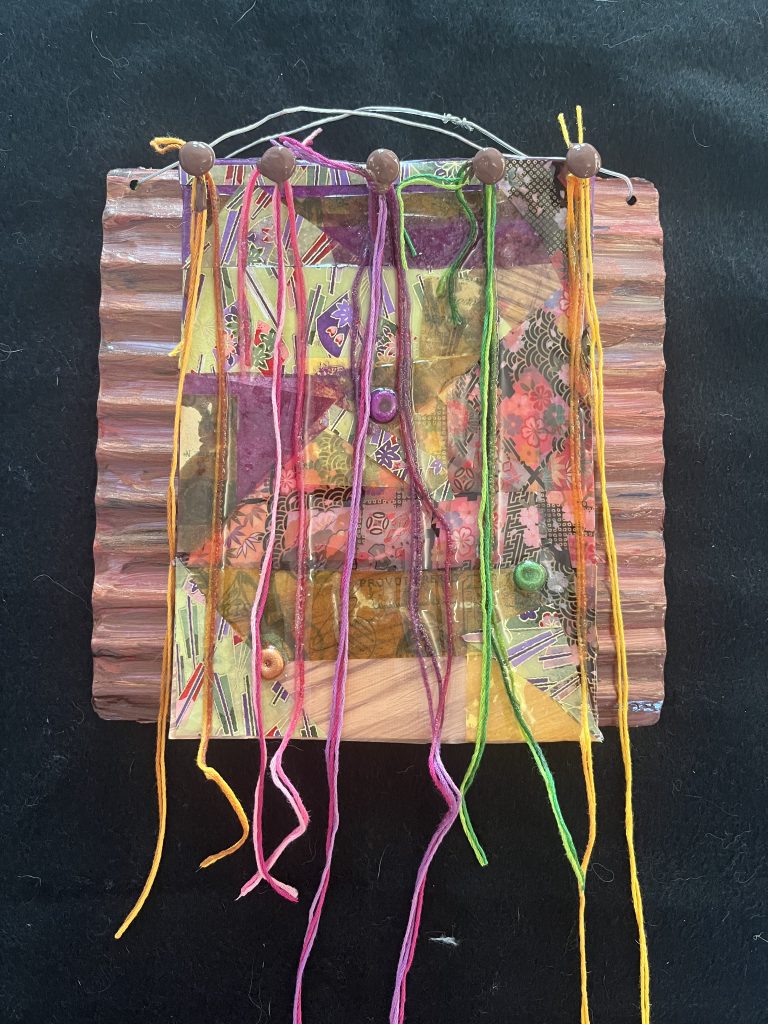

Karen Gross, Mending Art (2024)

Common Objects

Much of the art displayed here uses common objects, making it vastly easier for students and educators to find: forks, zippers, buttons, thread, yarn, rocks, paperclips, labels, glue and paint. With these common objects, we can create art that responds to the trauma we are experiencing – both representing the trauma itself and our pathways forward through mending.

As my students of all ages used art, I too expanded my art repertoire. I, too, used shards and common objects. I used ripped paper and glue. I used plaster of paris; I made fragile bowls and when they broke, I turned them into Georgia O’Keefe-esq sculptures. I used things that were discarded. And from the detritus, I created art that messages. And I shared it with students and educators.

Karen Gross, Fragile Bowl

Karen Gross, Georgia O’Keefe Series 1 (2022)

Art can help us both recognize and ameliorate trauma. I cannot think of anything more powerful than enabling all individuals to move forward through difficult times. Art is one strategy for doing that. We would be wise to recognize art’s power and not marginalize it. Art, as described here, is not static; it is created to help move people and in that effort, it allows all of us to see and experience the effects of creativity and the power of the possible.

And, to that end, here is one final piece of art, exemplifying the themes presented here. Emotional stress, dangling with uncertainty, piecing things together and finding beauty. Some say we are living in a VUCA world – with the letters standing (depending on the source) for volatile, uncertain, chaotic and anxiety-provoking. And, if you are doing trauma art—whether for yourself or for your students—reach out. I’d welcome that. Share it. It will help us all.

Karen Gross, Dangling by Threads (2023)

The Arts & Humanities Jury of The Delta Kappa Gamma Society International is pleased to announce the publication of ‘Plated Pair of Pears’ by Karen Gross in the DKG Gallery of Fine Arts, an online gallery of works of art and letters at https://gallery.dkg.org/index.php/sculpture/. Karen Gross, a resident of Boston, Mass. And Washington D.C. is a member of Washington D.C. Chapter of the Society.

DKG is a professional honor society for women educators with more than 55,000 members. Established in 17 member countries around the world, the Society defines its mission as promoting professional and personal growth of women educators and excellence in education. Society headquarters are in Austin, Texas, where Dr. Annie Webb Blanton founded the Society on May 11, 1929.

Author and educator Karen Gross has been awarded a $5,000 grant from the Mass Cultural Council. With the grant, Karen will be leading trauma recovery projects with students and educators in Boston and Danvers public schools.

Mass Cultural Council’s Cultural Sector Recovery Grants for Individuals offers unrestricted grants of $5,000 to creatives and gig workers to support recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and set a path for growth.

A list of all the grant recipients may be found on the Mass Cultural Council website.

I have been approached by many people recently about dysregulation. Students are dysregulating. So are educators. So are parents. So are families. So are individuals in relationships. So are workers. So are travelers. So are drivers of vehicles. So are folks across our nation.

Look at the above image. On the left side at the bottom (as you look at the image), there is order (not everything is identical importantly). Things are regulated. Items are in rows. Sure, there are some differences (like there are among us) but order is present. On the other side of the image, things are disordered. The squares are of different sizes and colors and they are not aligned. The spacing of the squares is off too. The squares are, then, what we can call “dysregulated.”

Ponder that idea as we consider what dysregulation looks like in individuals.

Dysregulation occurs when a person has an “outsized” reaction to a current event or trigger (outside the “norms” within our society), and they are then unable to control their behavior, at least initially. Dysregulation can take many forms, including shouting, hitting, agitation, extreme anxiety, throwing things (or oneself), nasty commentary involving vituperative words (and words can surely hurt). To be sure, dysregulation may look vastly different when exhibited by children, adolescents, young adults, more mature adults or seniors.

Consider the young child who has a temper tantrum. That is dysregulation. The youngster who holds his/her breath until he/she turns blue is dysregulating. The student who throws a chair or repeatedly pounds on a desk is dysregulating. The student who breaks a window or punches a hole in a wall is displaying dysregulation. The student or worker who disrupts a class or a work shift by throwing their body or their words around at others so that peers cannot do their respective work is dysregulated. The adult who screams and turns red and spews spit is dysregulated. The adult who taps his/her car on the back of another car to show displeasure with the other driver’s behavior is dysregulated. The adult who pushes in a line and tramples other to get attention is dysregulated. The senior who hits medical caregivers or a spouse is dysregulated. The senior who barricades an exit from a location is dysregulated. These are but a few examples.

If a person has “squares,” (meaning behavior patterns), dyregulation moves their squares into different places in space. Rather than some order (although note again that the ordered squares are NOT all the same), the squares fly out and flip out.

Not only can dysregulation take many forms but the reasons for the dysregulation are not uniform either (neither are the solutions). Individuals can be dysregulated due to mental or physical illness. Consider the impact of brain injuries as one source. Individuals who lack appropriate social-emotional learning can become dysregulated when they can’t manage their feelings with respect to a new situation. Individuals who are traumatized can dysregulate as a symptom of trauma, whether that trauma is occurring now or is older but is being retriggered by a current happening. And, the triggering trauma can occur from many causes (or multiple simultaneous causes) including sexual abuse, addiction, death, short and prolonged separations from loved ones, war, violence (including domestic outbursts), lack of parental love, care and security, neglect in early childhood.

It is these observations that should lead us to ask, when confronted with a dysregulated person of any age, NOT what is wrong with you but WHAT happened to you, noting a book of the same name co-authored by Oprah. To be sure, it doesn’t help to shout out “What happened to you?” in a nasty or demeaning or frustrated tone. How we enable someone to re-regulate who is dysregulated isn’t a one size fits all answer.

But, in our world today with its plethora of trauma, we would be wise to give educators, social workers, service workers, workplace leaders and healthcare givers tools they can try to re-regulate a dysregulated person. Sadly, we often don’t teach those skills.

That said, there are others who are very capable of re-regulating troubled kids and adults although they may not know or name the strategies they are using; life-experience has been their guide or instinct or personal experience. For this latter group, understanding why what they are actually doing that is working is helpful too. If you can name what works, then you have a way of understanding why a given strategy is beneficial and when it is best deployed. And, one can be prepared (more on that later).

One added note: Just getting angry is not being dysregulated. Anger is an emotion that is acceptable (and even good) to feel if the anger can be controlled. For example, someone who consciously writes an email that is angry to their boss or in a relationship is not dysregulating. It may be unwise or unnecessary and there may be better modes of expression but that is not dysregulation; this isn’t about NOT getting angry.

Rather, the dysregulation we are addressing here is about expressing feelings and emotions (often unidentified) in ways that are not within the norms of behavior of our society (other cultures may have different approaches) and are disruptive and uncontrolled and often generate both physical and psychological indicia.

Consider an adult who is so anxious that she/he cannot function; they cannot concentrate; they cannot work; they cannot communicate verbally or in writing; they are pacing and they are unable to identify what is troubling them; they are having a panic attack of sorts. This IS dysregulation. There may be many causes of which trauma is but one. To be clear here, anxiety per se is not bad; it is the height of the level of anxiety that can take it outside the range of what is healthy and manageable.

This discussion about dysregulation in the context of trauma isn’t about pathology or mental illness. Dysregulation is about responses that are not controllable, not understood, not manageable and that stand in the way of an individual processing what is happening in their mind and body. And oft-times (but not always), dyregulation is a behavior that bespeaks trauma.

Re-Regulation Tools in the Context of Trauma

Remembering that there is no one-size fits all solution to dysregulation, let’s start with this distinction: there are differing approaches to dealing with dysregulation where the individual dysregulating is presenting a danger to themselves or others.

In these situations, we need to create safety for everyone and that may well involve removing the dysregulated individual from the group (sub-optimal though that is from a trauma recovery perspective.) For situations where the dysregulation is disruptive and disturbing (in many senses), there are a differing set of strategies. It is this latter category of dysregulated individuals that we are focusing on here.

To be clear: Preserving safety for all has primacy; so again, if the dysregulation presents a clear and present danger to anyone (including the person dysregulating), then that takes priority. But, that is not our topic here.

Start with Prevention

Before we turn to dealing with a dysregulated person, I want to spend a few minutes (words/ideas) on our capacity to notice that dysregulation is on the horizon. This matters because it is easier to help someone who is on the road to dysregulation rather than someone who is already totally dysregulated. Think about it this way: if we can identify the tell-tale symptoms of a heart attack and intervene, that is vastly better than trying to restart someone’s heart after it has stopped beating.

To be sure, there may not be enough time to notice shifts or read clues and messages that are being demonstrated or evidenced by someone who will dysregulate. That said, it is always better to prevent dysregulation if possible.

Start with this reality: dyregulation is not as common if the “adult in the room” is calm and role modeling calm continuously. Dysregulation is also not as common when trust exists between the “adult in the room” and students/ workers/patients. Dysregulation is not as common if the “adult in the room” knows something personal and important about those for whom he/she is caring/teaching/serving/working. Dysregulation is not as common if the “adult in the room” has quality communication with those whom he/she is caring/teaching/serving/working.

Pause here for a moment. The just described actions/knowledge/activities can be viewed as tools to prevent dysregulation. But, and this is important, even with these tools, dyregulation can and oft-times does occur. It is no one’s fault. It often occurs without warning and without explanation (at least initially). Most of the time, dysregulation is done without intent; meltdowns are not planned for events. In a sense, it is similar to criminal law where intent matters before we punish. In the context of dysregulation, with rare exception, the “bad” behavior is neither planned nor intentional.

Finding Clues

Now, these are not the only tools that can help prevent or minimize dysregulation. Notice that the above suggestions are largely in the control of the “adult in the room.” What follows are concrete hints that the “adult in the room” can look for in those whom they are educating/serving/working. And, here’s an acronym to help one remember these clues — and they are only clues. Sometimes, the clues can lead down a false pathway. Sometimes they are suggestive but not definitive. Use them, recognizing they are neither the be-all, end-all nor a complete listing of possible clues. And, above all, don’t blame yourself if you miss or misunderstand a clue.

The acronym is: SHOW. As an overview (with explanations to follow), the “S” is for Square Sampling; the “H” is for Hypervigilance; the “O” is for ordered/disordered; and the “W” is for Wandering (eyes or body parts or the whole body). And the word “SHOW” has meaning too — because those who may dysregulate may SHOW their cards (so to speak) before they dysregulate fully and completely.

“S”

Square Sampling refers to how the “adult in the room” looks over and observes those who are there. It starts by looking in the 4 corners of a room and then creating a square as one looks down the back row, down the side rows and then across the front row. One might be amazing by what one notices if one observes with intentionality. (This works in all shaped rooms and all seating arrangements.)

I became familiar with this approach based on a video taken of me teaching some years ago where I was being critiqued (at my own request I might add). What I saw, and I never would have admitted this had I not actually seen it on tape, was that I taught primarily to the right side of the room and within that, I focused on those more of less between the front and the back. Are you kidding me? I would have said I teach to all corners of the room but I wasn’t doing that. The educator critiquing me said: teach (or speak when giving a presentation) to the four corners and develop eye contact with those in the four corners and then move inward. I surely had not been doing that.

While obviously this is not an engagement strategy for online learning or Zoom calls, it has real value for those working/teaching etc. in a room. And, I can vouch for the fact that it actually works to engage a group. People feel included and the person doing the Squaring can see who is not engaged. More on that in a minute.

“H”

Hypervigilance is not easily cultivated (and it has its downsides for sure). But, for those who have been traumatized, one of the after-effects is hypervigilance. Now, this means that if the “adult in the room” has had his/her own trauma experience that he/she has processed, it may be easier to detect dysregulation in others.

Hypervigilant folks can detect early on if something is off in the tone, style, atmosphere in a room. Hypervigilant folks can sense when a person is struggling, sometimes before the person him/herself may realize. The hypervigilant person can look around a room and get a feeling about those in the room who are stressed or anxious or struggling. A hypervigilant person can detect when a personal relationship is going off the proverbial rails (don’t I know!). It is as if their own trauma has given them a telescope that allows them to recognize trauma in others.

“O”

The “O” can best be understood by returning to the image at the start of this article. If the “adult in the room” observes that someone is struggling to find something in their backpack or desk or purse or, alternatively, their things are all disordered as they unpack and get ready to start their day, this might signal that what preceded entry into school or the workplace or the medical setting was not optimal. We get anxious and flustered and stressed when things happen to us and we carry those feelings with us into where we are going.

By way of example, if a child has witnessed a huge fight between her caregivers at breakfast and was also rushing to get to the school bus, that child may enter school not ready, willing and able to learn. She/he needs to process and reset based on the breakfast that occurred. And, the child may not realize how affected he/she was by what she/he witnessed. (Infants are often aware of parental stress too even if they lack the words to express what they are hearing and seeing and sensing and smelling. An example would be a new mother struggling to nurse. The infant can sense the struggle and that may account for the infant’s crankiness and unease. Yes, it could also be a wet diaper or an allergy to the supplemental formula.)

My book released in 2020 is titled Trauma Doesn’t Stop at the School Door references the just described phenomena. We may not know what is happening to us, we may not have words to describe it or we may even have normalized it. But, we carry an invisible backpack wherever we go and some backpacks are bigger than others. For a remarkable story about the invisible backpack of one individual, read Calvin Trillin’s Remembering Denny, a book that even on re-reading captures my heart.

“W”

The “adult in the room” can also gauge whether folks with whom they are working are engaging with them. Are someone’s eyes wandering? Are they focused on the outdoors, not what is going on in the room? Are they looking down? Are they glued to their devices (phone; Ipad etc)? Are they fidgeting too much in their seat or have trouble getting seated? (This is why fidget toys work.)

The just described wanderings may (but not always) suggest that a person has experienced something untoward or remembered something untoward recently. When we disengage or when we don’t connect, that is a signal because our brains are wired for connection. When we disconnect (which is one of trauma’s hallmarks), wandering is what we do.

These wanderings — the inability to connect with another person right then — are a message. It is not a message “to leave me alone.” Indeed, it is a message saying “I need you to connect with me.” The problem, of course, is that on the surface it appears that the affected person wants to be alone; but, that is a facade for the reality that they feel alone and want to find an anchor, a way to connect again. And, if a person stays disconnected, it is way easier to dysregulate.

Bottom line: If we see one or more indica of SHOW, we have a warning sign that a person is struggling. And, before things get totally dysregulated, we can try to connect through words or eye contact or a touch on the shoulder (being cautious about touch in many settings).

Sometimes, if the adult in the room senses lots of children/adults with SHOW symptoms, they can pause what they were doing and engage people in an exercise that lowers anxiety and stress and even distracts someone from where they were sitting mentally. And, one other point before we move on, NOT seeing SHOW is not a sign of failure; it is often hard to see/hear/ experience. And also, in some instances, SHOW may not even occur or may be simultaneous with the dysregulation.

Self-Identification

One added point. There are opportunities to help those who could dysregulate self-assess and even see the clues in their own behavior that signal that a “meltdown” is approaching. These folks can then reach out to the “adult in the room” to message: “I am about to dysregulate. Help me.” These individuals can even ask for objects like fidget toys that will allow them to find a way to pause; they may decide to do a breathing exercise.

To be sure, this requires substantial pre-dyregulation intervention. But, the self-messaging has value and is, at the end of the day, what we hope most folks can learn to do. Elementary school teachers actually teach students emotional regulation as part of what they do regularly, even in a context not involving trauma.

While beyond the scope of this article, there are strategies that can be taught to individuals who are likely to dysregulate. They can use a hand signal of a flipout (fingers open and stretched into a fan). They can have a key phrase or word: “It’s happening” or “I’m flipping.” And eventually, the controls can become internalized.

But, there is a caution here. If someone who is dysregulating sublimates the desire or finds a way to cabin the uncomfortable feelings he/she is having, that is not success. The absence of processing and naming and understanding is damaging. There are people who don’t and can’t get in touch with their feelings but rather than dysregulate, they unconsciously hide those feelings. Then, the feelings can emerge later in unrecognizable forms of insecurity and anger and guilt and anxiety. The latter can produce many negatives, including the ability to move forward freely and unconstrained.

Overregulation is not a gift and it is as damaging as dysregulating although vastly more socially acceptable. But the price tag is high because overregulated individuals will, down the road, need to let the sublimated/repressed feelings out and if they have persisted since childhood or over decades of a flawed relationship, then the later release has deep consequences. Relationships and marriages and work can be disrupted or even terminated. So, helping an overregulated person disinhibit is a task worth undertaking, but it requires in most instances professional help and time.

Strategies for Re-Regulation in the Context of Trauma

What follows are a set of strategies that can be tried to re-regulate an individual who has become dysregulated due to trauma, remembering that there can be many other causes of dyregulatory behavior. Trauma is our context here. They are not listed in order of importance or success; they can be combined; they can work for some folks and not for others; they can be adjusted based on race, gender, ethnicity and culture. These strategies are fluid in the sense that context matters; causation matters; the affected individual’s experiences and levels of processing matter. And, recall too that these are not strategies for when there is a real threat to the physical safety of the dysregulated person or others in their midst.

Calm

As noted earlier, it is critical that the dysregulation not dysregulate the “adult in the room.” Re-regulation requires that the dysregulation be seen for what it is: a behavior that is a cry for help or attention or engagement. If the “adult in the room” becomes dysregulated too, that makes matters worse and things escalate. Yelling or even tone or body language of the “adult in the room” can exacerbate an already volatile situation.

Processing in Place

Since a mainstay of trauma is disconnection, it is best to help the person who is dysregulated to process in place rather than removing them from the room. We are prone to “punish” those who act out by separating them, putting them in a corner, sending them to a principal or a supervisor. We even try ignoring them, hard though that is. All of these activities truncate connection when what we need to establish is connection.

Processing in place is not easy but it has many benefits. For starters, it builds connection. Second, it enables others witnessing the dysregulation to see how re-regulation can happen. It also does not pathologize the negative behavior; it sees it for what it is: a response to (a behavior caused by) trauma.

For processing in place, it may be useful to bring in a third party who can help either with the person dysregulating or the others in the room. To be sure, this needs to be part and parcel of institutional culture; one can’t “cold call” someone to help. If trained, the person helping can enable processing to happen faster since there are more hands on deck so to speak.

With processing in place, the dysregulated person is helped by the adult in the room to re-regulate through a series of interventions, as described below. The key here is to let the dyregulated person know that you know how to handle this and many people actually are wonderful at re-regulation, whether learned by experience or through instinct. And, while they may not have a name for the intervention they are providing, many adults can help other re-regulate.

A note: After the re-regulation process succeeds, the person who is successful in intervening may feel a bit strung out or fatigued or stressed. That is only natural as crises often hit the people helping after-the-fact. Think about medical emergencies or crisis management; the events can be handled but there are after-effects.

Asking Questions

The adult in the room can ask the dysregulated person some questions, phrased well and with a tone that is not demeaning or angry or anxious or frustrated. Consider questions like: “Is there anything I can do to help you?” or “Do you want me to get you something? or “Is there some music I can play that will make you feel better?” or “Do you want to share what is upsetting you?”

Not every dysregulated person is willing or able even to address these questions. They may be too out of sorts to listen; their cognition may be shut or shutting down. Their limbic system may be overloaded. Their diecephalon region may not be sending signals for re-regulation but instead may be disabling the management of emotions and body impulses. Their primitive brain stem with the five “f’s” may be at work: fight, flight, freeze, fawn and faint.

So, the asking of questions only works if a person who is dysregulating can process the questions.

If Questions Don’t Work, What Might Work Instead

If questions are not a useful tool, the adult in the room can try distraction. Consider providing some sort of object to squeeze or some object to spin or turn. Consider clay. Colored pencils may work to enable someone to draw. Consider puzzle pieces that can be put together or paper clips that can be connected to each other.

Any activity that allows for distraction and connection are beneficial. I have thought about (but have not used) bean toss games where the dysregulated person throws bean bags into a wooden stand, often depicting something fun or funny. Throwing itself is useful. Aiming for something (other than a person) is helpful. Using one’s body is helpful.

Connection, the end goal here in addition to re-regulation can be fostered in many ways. The dysregulated person has likely disconnected from you and the planned work/activity/assignment. You can connect at a physical level by approaching someone gently. Soft touch works too, messaging “I hear you” and “I am here for you.” Physical activities that allow for and enable connection are quality surrogates; putting together Legos or connecting straws or pipe-cleaners can help. And it helps if these strategies have been explained before dysregulation occurs; in other words, we can educate ourselves about dysregulation so we recognize it and know that someone will come to our aid.

Remember, behavior is the language of trauma.

One can also use affective statements like: “I understand…” or “I appreciate” or “I recognize” or “I see that” or “I am worried that.” These are all ways to message: I care, I know you are struggling and I am here. The use of the “I” allows for connection and showcases care.

One can also use feeling identification strategies (it is good if there has been a development of understanding and expressing and recognizing feelings both positive and negative): “I can see that this isn’t easy for you.” or “I can see that you are angry and frustrated.”

Another added tool is choice. Part of the problem with dyregulated people is that they are out of control and feel that they have no control. One way to restore control is to move the locus of control to an internality.

One can do this by giving the dysregulated person a choice: Would you like to move your seat or take a break for a few minutes? Or: Would you like to do something else for a few minutes or have a drink of water? Or: Would you like to move to my desk and I can move to yours or do you want to stand and balance on one foot for a few minutes? Or: Do you want to do the 4×4 breathing exercise (four in — hold for four — four out — hold for four) or listen to music for a few minutes with your headphones? Or: Do you want to play that game on your phone for a bit or send me a text? Or: Do you want to do the 3–2–1 breath exercise (inhale for three — hold for two — release for one) or jog in place?

Now the choices have to be realistic and ideally, they promote regulation. Balance does that. Changing physical space does that. Breathing in a pattern does that. Physical activity that is within bounds helps. Art helps. Distraction helps. Stress toys help.

If At First You Don’t Succeed

Not all strategies will work and not all strategies will work immediately. When someone is dysregulated, time seems to change for them and everyone around them. Even if the event is only over several minutes, it feels and seems and is experienced as a much longer time. (Time has this odd behavior; the same length of time can move fast or slow or evenly, depending on context and feelings and cognition.)

One activity to try in advance is measuring time with students/workers. Use an egg timer. Have them guess with their eyes closed when a minute has passed or three minutes. Silence makes this exercise hard. If music is playing or talking is going on, it is also hard. What the exercise shows people is the fluidity of time.

Indeed, I keep several sand timers available. One is 15 minutes and one is 30 minutes. I use them (even seeing them helps) to remind myself that time changes depending on mood, context, emotions,

Create a box or bag with feelings in it that are identified. There are emoji dice. There are Kimochi. There are cubes with feelings showing. When a person is dysregulated, let them find (identify) what they are feeling by looking into a mixed bucket of feelings. That is easier than actual naming.

Another option is to have a bucket of feathers available. Allow the dysregulated students/workers use feathers on their wrists or neck or arms. The tactile sensation helps calm the autonomic nervous system. Pre-prepared trauma toolboxes help too. The adult in the room can say: Just pull out your break box (or whatever one calls it) and use it for a few minutes.

Another option is to have dysregulated folks do something with their non-dominant hand or leg. For example, have someone trace their dominant hand with their non-dominant hand. Or balance on one’s non-dominant leg. Or write something with one’s non-dominant hand. The bottom line is that these activities require one to pay attention to something other than one’s current behavior (because otherwise the task cannot be done) and they open new neural pathways that allow someone to connect better to themselves and others.

Prepare Prepare Prepare

I have often said in the context of trauma memorials or anniversaries that planning is key. Once the anniversary arrives, it is too late to plan. The same is true in the context of dysregulation. If one is prepared for it to happen, then one is better able to handle it. This means identifying strategies and techniques before there are problems. They can be part of teacher training or workplace training.

And, it is wise to share them in advance with other affected groups — including the potential dysregulated individuals themselves. If they know in advance what guidelines exist and that if there is a breach how that will be handled, they are already in a better place. And, those who might become dysregulated need to know that they are not bad; it is their behavior that is troubling. And, they need to know that they will be supported as they navigate traumatic symptomology — including dysregulation.

We live in a world in which many people are dysregulated. Rather than pathologize it, we would be wise to share how to handle it. That will provide us with a vastly better way of navigating forward.

To return to the image at the start of this piece (which appears below again), we can become disordered. And we feel better when we are ordered (not as in over-orderly or over-regulated or hyper-neat or compulsive). We can sense and feel when our “squares” get jumbled and when they do, we are asking others — without words — to help us. And, with training, the adults in the room can help and the rewards are wide spread, not only for the individual dysregulating but for those witnessing it and those with whom the dysregulated person will engage later that day and into the future.

PS. To the person with this piece of art hanging in his home, I hope it brings you a sense of order when your world feels disordered.

https://karengrossedu.medium.com/behavior-is-the-language-of-trauma-ab9ba15b7071

Karen Gross of Gloucester, MA (1st row, 2nd from left) joined the U.S. Army War College student body for the National Security Seminar, June 5-9, 2022. Selected representatives from across the United States were invited to join the graduate-level seminar and exchange thoughts about national security topics in the capstone phase of the USAWC graduate program.

Carlisle Barracks, Pa. — Karen Gross of Gloucester, MA participated in the U.S. Army War College annual National Security Seminar in Carlisle, Pa., June 5-9, 2022.

Gross was one of 168 business, government, academic and community leaders selected from across the country to take part in the week-long academic seminar alongside the students of the Army War College. During the special academic event, Gross represented fellow American citizens in discussions with the next generation of senior leaders of the U.S. Armed Forces. For the senior military leader-students, these exchanges enable a deeper understanding of perspectives from across the American society they serve. The National Security Seminar was the capstone event of the Army War College’s 10-month curriculum, just before the Class of 2022 graduation ceremony to confer the USAWC diploma and master’s degree in Strategic Studies.

The Army War College executive seminar introduces NSS participants to contemporary issues and the next generation of senior leaders in the US military and national security agencies. In turn, the US and international students learned diverse citizens’ perspectives on the nation’s priorities.

Each of the four NSS featured speakers addressed an Army national security priority: former NATO Ambassador Ivo Daadler, president of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, on America’s role in the world; Prof. Rosa Brooks, Georgetown University Associate Dean, and Professor of Law & Policy, on future forecasting; retired Lt. Gen. Thomas Spoehr, Director of the Heritage Foundation Center for National Defense, on the viability of a military career in the 21st century; and Mackenzie Eaglen, Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, on credible combat power.

National Security Seminar days are structured around daily presentations about an issue of national security significance, followed by candid discussion in a seminar with students representing the U.S. military students, representatives of US Government agencies, and international officers in the student body. NSS days provide guests with extensive academic and social interaction with Army War College students, who represent senior officers in the U.S. Army, Air Force, Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, and other nations’ armed forces, with senior federal agency civilians.

The mission of the U. S. Army War College since 1901 is to enhance national and global security by developing ideas and educating US and international leaders to serve and lead at the strategic-enterprise level.

The Army War College resident education program, which sponsors NSS, is the signature program among its multiple education programs for strategists, senior leaders, and Army general officers.

Karen Gross’ books … leave you hanging on every word. She always captures you, embraces you, educates you and leaves you with a huge smile on your face with a sense of understanding and total glee.”

— Jackie Coogan, Adjunct Faculty, Bunker Hill Community College, Spring 2022

BOSTON, MA, USA, June 22, 2022 /EINPresswire.com/ — Two educators have co-authored a story, which they and their children and grandchildren illustrated, about a pocketbook. My Pocketbook (on sale June 30) is the story of why we carry pocketbooks, what we place in them, how we worry if they are lost and how they give us comfort. In these difficult times in our nation and across the globe, pocketbooks can be characterized as transitional objects, helping us feel at home whether we are at home or not. Pocketbooks enable us to deal with separation and its anxiety. The story also touches on teasing and bullying, a far too common phenomenon.

The story is followed by a series of questions to engage readers young and old. There are opportunities for readers to share their own stories, create their own pocketbooks and unravel the history of pocketbooks – they originated centuries ago and were also used by men! This story is trauma-sensitive, specifically designed to encourage engagement, connection, creativity, and a deep belief in the power of lessening trauma’s impact, including through stories told and retold and shared and reshared.

About the Authors

Susanne Demetri is a retired religious educator who has also volunteered at nursing homes in MA. She is the inspiration for this story, and some of the illustrations were created by her granddaughter, Mabel.

Karen Gross is an author, educator and artist who specializes in trauma and has written both adult and children’s books. She has illustrated some of the pocketbooks in the story. Sue and Karen are next door neighbors and consider themselves two lost sisters that were meant to find each other and did. Learn more about Karen Gross at http://www.karengrosseducation.com.

The book is available in digital format as well as print through Amazon.com and other retailers.

Paperback $19.95

https://www.amazon.com/My-Pocketbook-Karen-Gross/dp/B0B39KRD38

Kindle eBook $9.99

https://www.amazon.com/My-Pocketbook-Karen-Gross-ebook/dp/B0B2SF24LZ

This book’s audio version has been produced in partnership with Insight for the Blond – so that all may read. To learn more about Insight or to support their mission, visit www.insightfortheblind.org.

My Pocketbook is narrated by Wendy Sager Pomerantz and was edited and produced by Matt Corey.

The book may be listened to at this link for free: https://youtu.be/2NLRBmkUHIk

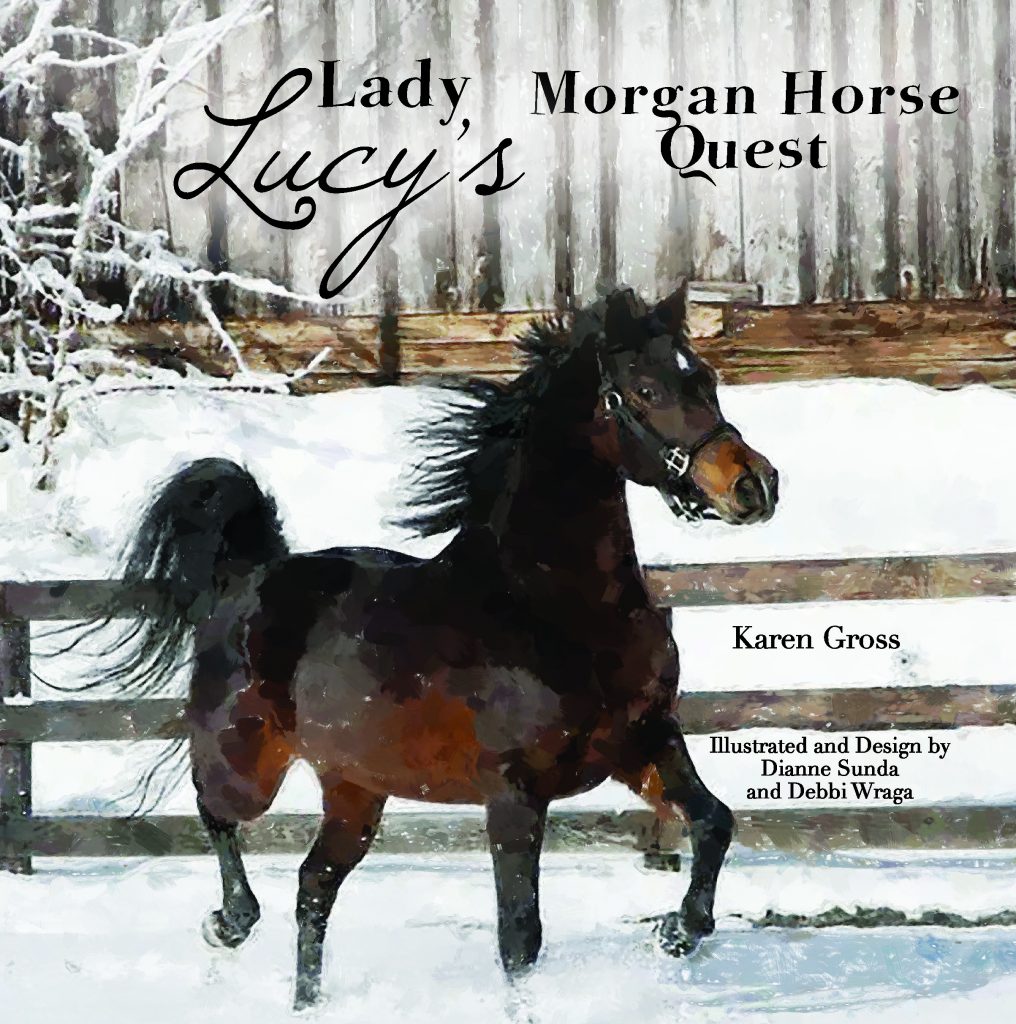

When Morgan the Horse is Gifted to Lady Lucy’s Team They Begin a Quest to Free Trapped Horses to Lift the Town’s Spirits

Gloucester, MA – January 18, 2022 — A timely new book in the Lady Lucy children’s book series, author Karen Gross has written a story that enables children to see how teamwork can restore the joy in the life of villagers.

With the help of her trusty team of Dillon the Dragon, Tapestry the Unicorn and Quincy the Belgian Sheepdog, the series’ multi-racial heroine Lady Lucy tries to solve a decades-old mystery. With the aid of a horse named Morgan, they find a way to work together and restore the joys of life that isolation and famine have taken away.

With a subtle Pandemic theme, trauma-sensitive approaches and glorious illustrations, this is a book that can be read to, with and by children. Consistent with the other books in the Lady Lucy series, this story engages the reader in the Quest, enabling everyone to follow the pathway to success and the power of the possible.

Amazon purchase link: https://www.amazon.com/Lady-Lucys-Morgan-Horse-Quest/dp/160571612X

For more information about Karen, please visit her website www.KarenGrossEducation.com.

About the Author

Karen Gross is an author, educator and storyteller. Previously, she was president of Southern Vermont College in Bennington, VT and served as a Senior Policy Advisor to the US Department of Education. Prior to that, she was a law professor for 2 decades focusing on asset building in low-income communities. Currently, she is Senior Counsel to Finn Partners where she specializes in crisis management. An expert in trauma and disaster planning and relief, she is certified as a PFA (Psychological First Aid) provider and teaches in a clinical certification program in trauma at the Rutgers Graduate School of Social Work.

She is the author of a recent adult book on trauma released by Teachers College Press in June 2020 titled Trauma Doesn’t Stop at the School Door and a series of auxiliary activities to promote student success, all available at www.karengrosseducation.com. Karen resides in Washington, DC, and Gloucester, MA, home to some fish and lots of swamps.

Contact: Karen Gross, 917-363-4872, karengrosscooper@gmail.com

Author; Educational Commentator

Senior Counsel, Finn Partners

Washington, DC

Twitter: @KarenGrossEdu

Gloucester, MA – November 15, 2021 — Author and education consultant Karen Gross will be selling trauma supportive acrylic work on canvas and prints on canvas to benefit the Virtual Teachers’ Lounge (virtualteacherslounge2021.com) a program that supports teachers.

Among the works being sold are her series of multimedia works called Don’t Erase Me – a Pop Art inspired series that use the pointed pink cap eraser suggesting that although erasing is useful for rubbing away errors in schoolwork, the issue is more complicated regarding personal stories and trauma in schools.

Links to all the work on sale may be found through the Facebook Marketplace associated with Karen’s professional page, located at www.facebook.com/karengrossedu and by searching Don’t Erase Me in the Facebook Marketplace. This special fundraiser runs through December 15.

View Karen’s signature piece You Can’t Erase Everything here:

https://www.facebook.com/marketplace/item/619829035709226

View other works from the series here:

Mellow Yellow: https://www.facebook.com/marketplace/item/1035462663909499

Mixed (Up) World: https://www.facebook.com/marketplace/item/2169631396508518

For more information about Karen’s art, visit her Facebook page www.Facebook.com/KarenGrossEdu and her website www.KarenGrossEducation.com.

The Virtual Teachers’ Lounge is a project founded by Ed Wang PhD, Pat Neal, Sakina McGruder and Karen Gross in 2021. It was formed to assist educators as they navigate these troubled times. In the Virtual Teachers’ Lounge educators can share how they are managing with students, share best practices, and receive peer support. All of the sale proceeds of the art in the Marketplace on Facebook go to fund the VTL, the costs of which include technology, gift cards for participants, promotional efforts and outreach as well as programming and materials. None of the founders are paid for their/our services.

Contact: Karen Gross, 917-363-4872, karengrosscooper@gmail.com

Author; Educational Commentator

Senior Counsel, Finn Partners

Washington, DC

www.karengrosseducation.com

Twitter: @KarenGrossEdu

917 363 4872